The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has led to many reports of increased stress, anxiety and depression globally. According to a report by the World Health Organization (WHO), the global prevalence of anxiety and depression had increased by ~25% during the first year of the pandemic. In addition, the International Committee of the Red Cross reported that internationally, people felt stressed, anxious and worried due to family being infected with the coronavirus, fear of getting the virus, and isolation and quarantine measures, which led to distress from separation with family members. Furthermore, research from the Harvard Medical School and University of North Carolina Chapel Hill found that other related stress factors included concerns regarding job losses and household income, as well as frustration and stress about not being able to socialize and enjoy usual activities.

Mental stress resulting from COVID-19

There were many reasons for the increased stress experienced during the pandemic. People were unsure about their own health and that of their loved ones. Many businesses were impacted, resulting in many losses in jobs and financial instability for families. Many companies had to adjust quickly to working from home and schools had to conduct their lessons online. In addition, the dynamic changes about the coronavirus and the pandemic, and later on about the vaccines, led to an infodemic in various media channels, internet and social media, and even friends, families and co-workers. When the governments from various countries started to enforce their national contact tracing, symptom monitoring and quarantine apps, many people were concerned regarding the strict surveillance methods enforced by the governments, which raised privacy concerns and further increased stress in individuals. For example, geofencing apps were enforced in India and Taiwan to create a virtual fence around people’s houses, and the authorities would be informed if the quarantined individuals disobeyed the regulations and went outside. On the other hand, other countries like South Korea, Poland and Russia also enforced their national quarantine apps with strict rules surrounding a quarantined individual. As an example, Poland’s Home Quarantine app required the quarantined person to take a selfie during random prompts to ensure that the person was at home. According to one of the app users, she felt stressed because she had missed several alerts in the morning and the police checked up on her at her home. Additionally, her stress was compounded because she felt that her freedom at home was compromised as she had to be on standby 24/7, even during a shower.

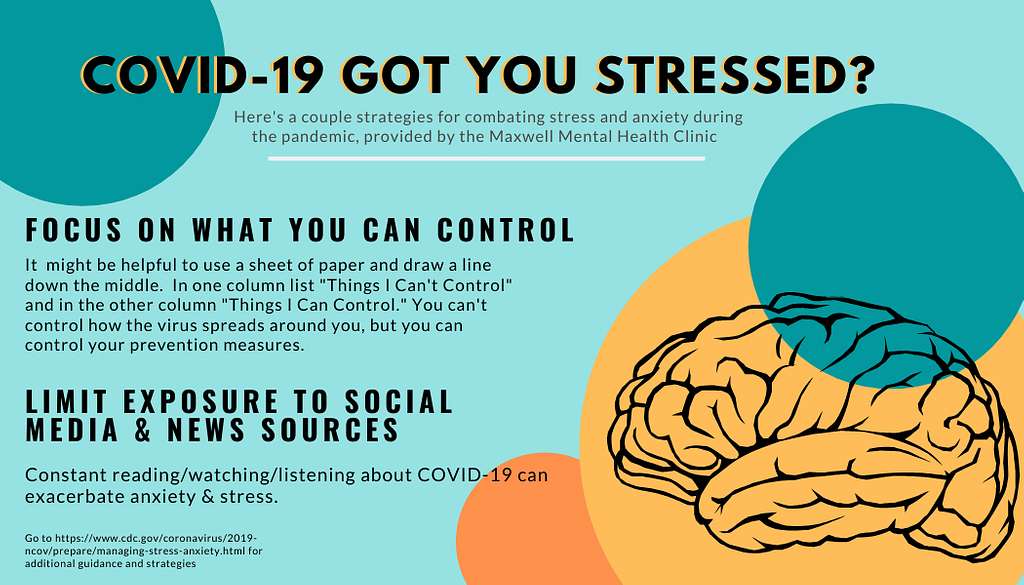

Stress management techniques

The Mayo Clinic has put forward some patient education materials to help the public to manage stress related to COVID-19. Individuals who experience emotional stress may exhibit signs and symptoms of irritability, sadness, grief, anxiety or fear. On the other hand, physical stress can manifest as tension, fatigue or sleep problems. Additionally, other stress symptoms include having negative or racing thoughts and worry or persistent worry, and behaviors related to social withdrawal, excessive checking, avoidance and seeking reassurance. The key is to keep track of one’s overall stress levels, know one’s stress limits and stay connected to supportive people around. Some tips suggested by the Mayo Clinic include:

- Maintaining healthy habits and routines, such as having regular sleep and exercise, eating and hydrating well;

- Staying connected with family and friends, as well as with social media and news (with occasional purposeful disconnections, if stress levels increase);

- Practicing relaxation methods regularly and throughout the day, such as relaxed/deep breathing, mindfulness and meditation, muscle stretches, listening to music or watching something light-hearted that makes you laugh, or even going for a drive;

- Being aware of your thoughts by listing your worries down and challenging these worries;

- Practicing kindness by being kind, patient and helpful to others, and working together as a team where possible; and

- Taking reasonable precautions to keep your daily life normal, and listen to recommendations by experts to keep safe during the pandemic, such as washing hands, disinfecting surfaces and wearing face masks, and avoid being paranoid or overly-cautious.

Mental health apps for COVID-19

The pandemic had disrupted many mental health services and increased barriers to treatment. Monitoring of patients was impeded by social distancing measures. The increasing amounts of stress, anxiety and depression was met with many digital health companies trying to get into the digital mental health space. Studies have shown that cognitive-behavioral therapy or CBT had the potential to treat such conditions. Thus, many of these companies started to develop their own mental health apps that claimed to be based on CBT. Of course, there are some that are evidence-based, and these apps have been tested clinically in patient populations. One such app is Wysa, an artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot that was awarded the US FDA Breakthrough Device Designation for use in adult patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, anxiety and depression. Wysa is an example of a line of upcoming healthcare innovations known as digital therapeutics. In essence, digital therapeutics is a subset of digital health innovations that have an evidence base that proves that these technologies are efficacious in preventing, treating and/or managing a medical condition/disease. Other apps that have become quite popular include Headspace, Calm and Happify, among others.

Quality of mental health apps for COVID-related mental health problems

Wysa has ~15 publications either published or in the pipeline, some of which are in collaboration with well-known partners like the UK National Health Service (NHS) and Harvard Medical School. Headspace, another mindfulness app, is also evidence-based, while the Calm medication app has also conducted cross-sectional surveys and randomized controlled trials among its users. Interestingly, very few studies (in fact, none to my knowledge) have tested or reported the long-term efficacy and/or effectiveness of such mental health apps. In contrast, there are many other apps that have targeted the mental health space, but with little evidence on the apps themselves. The persistence of COVID-19 has also led to new technology companies wanting to get a piece of the pie in the digital mental health space. Unfortunately, some companies have used what is called the “halo effect” to extrapolate the efficacy of mental health apps that has published evidence to their own apps. While there are studies that have compared various mental health apps, not all studies are congruent in their results. In fact, quality evaluation studies on mental health apps using the validated Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) tool have shown that although these apps have good functionality and aesthetic appeal to consumers, their information/evidence-based components were not as high. In a study that evaluated mental health apps available in Singapore, the authors reported that only 30% of the apps had good-excellent overall quality scores. Furthermore, 59% of the apps shared personal information with third parties and only 14% were compliant with data protection standards. Consequently, the top ranked apps recommended by the authors were Sanvello, Woebot, Happify, Youper and Bloom.

Considerations for designing evidence-based mental health apps

Here, I will describe several frameworks and models that I have used to design mHealth (mobile health) apps. Although these principles are guidelines for designing mHealth apps for medication management, these principles can be adapted by developers and user practitioners of mental health apps.

- Pharmacocybernetic Maxims: One framework that is useful for considering how mental health-related information provided by an mHealth app should be provided to users is based on the Pharmacocybernetic Maxims, which dictate four principles in terms of the quality and quantity of health information, its relation to target audiences and the manner of data presentation.

- Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory: When considering how the user would interact with the mental health app in the context of the environment, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory (EST) is a good model to consider. Digital health technologies do not exist alone, but depend on how users interact with them, and the types of environment in which the users use the technologies. The EST describes how the user interacts with the technology in a wider context of five types of environments – the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem and chronosystem. These environments can help developers of mental health apps consider both the short-term and long-term impacts of the app use by its users.

- UCD, ECD and ACD approaches:

- User-centered design (UCD) is the most popular and common design approach that designers use to develop digital health technologies. This approach focuses on users and their needs in each phase of the technological design (and truthfully, is the easiest to implement). However, in order to ensure that the mental health app being developed is sustainable in the long-term, designers should also consider experience-centered design (ECD) and activity-centered design (ACD) approaches.

- The second approach, ECD, is based on Norman’s principles of emotional design, which stems from our variations in responses towards everyday things. In ECD, there are three levels of emotional design – the visceral, behavioral and reflective levels. Readers can hear the keynote presentation by Don Norman himself at the O’Reilly Emerging Technology Conference (San Diego, CA, Feb 2004).

- The third approach, ACD, is perhaps the most difficult to implement and evaluate. Based on Leontiev’s Activity Theory and Engeström’s Activity System Model, the ACD approach focuses on the “activity”, which is the purposeful, transformative and developing interaction between the user, object (e.g. mental health app) and the world (which include any social context). This approach considers the real-life use of the object as part of the user’s interaction with the world.

- Intervention Mapping: The Intervention Mapping (IM) approach is a common health behavior framework that has been used in the development of mHealth apps. IM is based on a detailed list of behavioral change theories and it prescribes a specific set of 6 steps that are used in the context of developing interventions:

- Needs assessment / problem analysis

- Matrices of change objectives

- Select theory-based intervention

- Program production

- Adoption / implementation plan

- Evaluation plan

Summary

It is undeniable that COVID-19 has caused much stress, anxiety and depression in our daily lives, and mental health apps are becoming a widely used digital health commodity worldwide. A Google search will reveal many recommendation articles (e.g. Lifestyle Asia, Verywell Mind, Health Newsletter, Inc.com, Entrepreneur India) on what types of mental health apps are available. While some apps are substantiated with an evidence base, there are others that are rated highly in the app stores, but base their claims on the “halo effect”. There is no hard and fast way to determine which app is the most suitable for a user, but it is best to read the available evidence for the specific app that is intended, trying out the free/trial/paid versions of the app, and perform your own evaluations of the app based on quality assessment tools that are out there. In addition, users should also arm themselves with a repertoire of stress-relieving techniques to help cope during the pandemic. To this end, various organizations have provided their own self-care tips, such as Mayo Clinic, American Red Cross, MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Psychology Today. Stay safe and take care!