I had an epiphany yesterday when I was trying to read up on how my own work and practice was related to the medical humanities. To most clinicians (and pharmacists), medical humanities seem to be something that is “messy”, “fluffy” and “cloudy” – not a solid science. However, in my experience, especially with training the younger generations, teaching the hard sciences makes the younger “Gen Techno” healthcare practitioners lose sight of their “inner selves” and they miss the humanistic side of providing holistic patient care. And this is why the humanities are so important – in my opinion. Many healthcare educators are already acknowledging this, and that is why university curricula are trying to incorporate elements of empathic responding in their teachings. But the younger generations are usually healthy and it’s difficult for them to understand the challenges of patients’ lived experiences. While they can probably understand from a third-person view, it is different from truly putting themselves “in the patient’s shoes”.

What is Digital Health Humanities (DHH)?

While I am not a medical humanities scholar, I realized that some of the work that I have been doing is in the intersection of what has been defined as the “Digital Health Humanities” (DHH). According to the DHH guru, Professor Kirsten Ostherr, this is an emerging field that “blends critical analysis with the use of computational tools to explore research questions related to digital information and communication technologies (ICTs) in healthcare” [1]. DHH focuses on ICTs as objects of inquiry, and how such technologies can impact healthcare practice (in the broadest terms), patients’ healthcare journeys and healthcare education [1]. In DHH research, computational methods and digital resources are used by researchers to explore research questions that link healthcare technologies to the human experience of health and illness [2]. By engaging with stakeholders like patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers and other who are engaged in the holistic care of the patient’s healthcare journey, the social and technical features of digital health technologies can be analyzed through both quantitative and qualitative means to identify how these technologies impact the practice of healthcare. Hence, in my opinion, the DHH approach involves the use of digital and/or computational methods and tools to pursue humanistic research, and helps one understand how to bring back the “humanistic” elements in healthcare.

My Thoughts and Experience With Digital Health Humanities (DHH)

While listening to Kirsten Ostherr’s interesting lecture on “Digital Health Humanities: A Critical Intervention For a ‘Data-Driven’ Pandemic” [3], I realized that the work that I have been doing in digital health in designing user-centered and experience-centered healthcare innovations actually falls within this field of DHH. The interests that I have had in merging the social sciences with medical sciences has put me in this field unknowingly – thus I was already a Digital Health Humanities Practitioner all along…

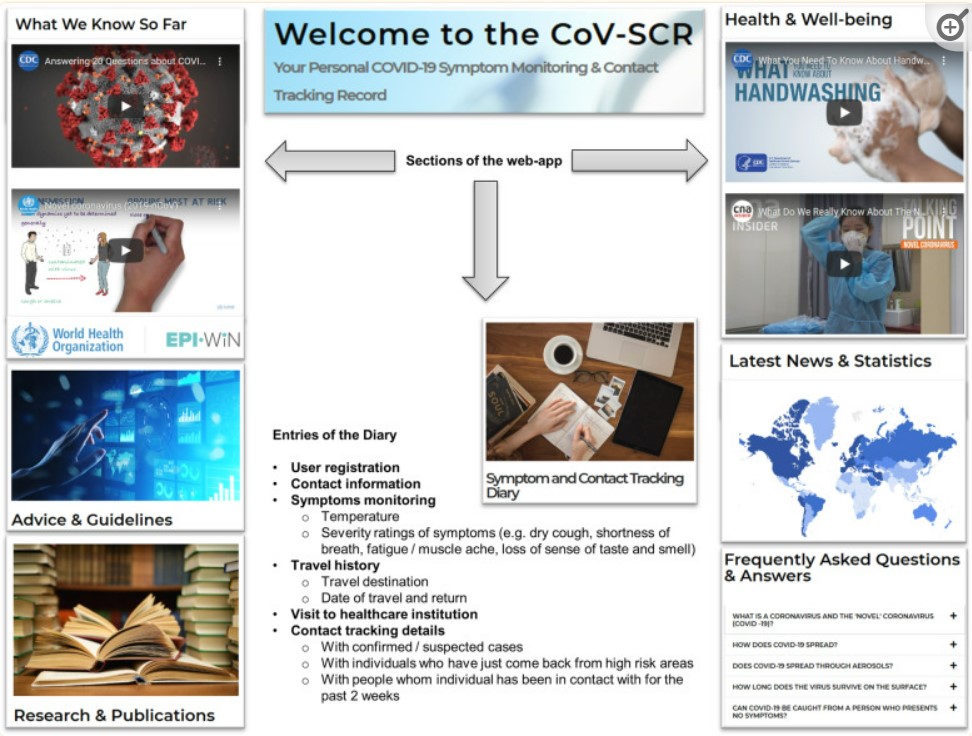

In-house Developed COVID-19 Self-Tracking App

During the start of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, I still remember that I was in Singapore flying back to Australia. Upon reaching Melbourne, which was when the first oubreak of the coronvirus was identified in Wuhan, I remembered that for the first few weeks, I would get “strange looks” from passers-by (particularly Caucasians) when I went out to buy my groceries – as if I was “one of those people” who would bring the coronavirus into the country. I felt uncomfortable and unsafe with the stares that I was receiving at that time, as it seemed like the coronavirus had led to racial/ethnic divide in the suburb where I lived in. During that time, bluetooth contact tracing (which was pioneered by Singapore) [4], was still not developed yet. Hence, using the concepts of user-centered design and a bottom-up approach [5,6], I developed a manual contact tracking and symptom monitoring app for myself and my other friends (Figure 1). Thinking back, it was through my own narrative as a minority demographic in my suburb suffering from the “mental trauma” of fear, stigma and my own emotions that gave me the impetus to develop the app. Perhaps it was the “humanistic” element of how such an app would provide me “solace” and peace of mind by performing my own contact tracking and symptom monitoring that provided me with that push to develop it. In order to determine what features would be useful in such an app for me and my friends, on hindsight, it involved an understanding of how the app would operate in a wider environmental context described by Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory.

Pokemon Go for Social Withdrawal Symptoms

I was also reminded of the news of Pokemon Go (Figure 2) – the famous augmented reality game that took the world by storm when it was first released in 2016. In Japan, it was observed that youth with severe social withdrawal symptoms (known as hikikomori) started leaving their homes to battle in Pokemon gyms with strangers [7]. Prior to playing this mobile game, these youths were unable to be cured by traditional psychiatric consultations. Since then, other serious games for healthcare, such as Sea Hero Quest for Alzheimer’s Disease, and EndeavorRx – the first FDA-approved prescription-based digital therapeutic for attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), have been developed. These games were able to impact changes in clinical practice and patient behavior, and are definitely worthy phenomenons for DHH study.

COVID-19 Apps Impacting Behavior and Emotion of Quarantined Individuals

During the peak of COVID-19, a plethora of mobile health (mHealth) apps flooded the app stores. These apps were developed by various individuals, companies and organizations, some of whom took advantage of the situation by creating fake apps, ransomware apps, or spread misinformation about the coronavirus, disease or vaccination information [10]. In a scoping review that we published in JMIR Nursing [10], we had interesting findings of some countries who came up with quarantine and geofencing apps (in contrast to contact tracing apps) that used bluetooth, Wifi or GPS to track user movements of those who were supposed to be self-isolating and quarantining at home. If the individual was found to flout the rules, police would visit their homes. This practice not only impacted user movements, but also restricted user behavior, and increased emotional tension and fear, as these users felt that they needed to be on standby 24 hours a day. In fact, some apps, like Poland’s Home Quarantine app, even requred the quarantined person to randomly take selfies to prove that they were at home, which brought about further questions on privacy and confidentiality of these quarantined people.

Since our review was published during the period when every country was trying to develop their own contact tracing apps, our publication was picked up by The Australian News and La Trobe University media, where I was interviewed on what makes a good COVID-19 app. In addition, during the peak of the pandemic, when Australians were envisioning a strategy to move towards a post-pandemic world, this publication led to an international Podcast Influencer who interviewed me as part of a larger group in his podcast series on “Imagining Australia – A healthy Australia in 2031”.

Quality of Digital Health Technologies and the Potential for Mis-information

As you would probably recall, there was a period of time where mis-information about COVID-19 and vaccinations were prevalent as well. This sparked a series of research projects done by my group on the quality of digital health technologies that were out there for a variety of conditions. For example, we found that in general, among the commercial digital voice assistants, Google Assistant and Apple Siri performed the best overall in terms of providing relevant, accurate, comprehensive, user-friendly and reliable information about COVID-19 [11]. Interestingly, Google Assistant consistently scored better than Google Home in the evaluation parameters. In another study where we evaluated COVID-19 vaccine information on video-sharing platforms [12], we found that YouTube videos had significantly higher quality scores than TikTok videos. Even though the accuracy of COVID-19 vaccine information were accurate for videos on YouTube, TikTok and Facebook Watch, TikTok videos had the highest understandability scores.

When the pletora of mental health apps started to proliferate due to the potential stress, anxiety and depression brought about by the pandemic, with changes to working patterns and lifestyles, our group decided to evaluate the quality of mental health apps out there for COVID-19 [13]. Our evaluation results showed that only 30% of apps for stress, anxiety and depression had good/excellent quality scores. Even though the apps scored well for functionality, they scored worst for information provision and engagement. The top ranked apps were Sanvello, Woebot, Happify, Youper, and Bloom. But majority of the apps still had room for improvement.

The varying quality of digital health technologies that we discovered for COVID-19 led us to explore healthcare technologies for other medical conditions, such as eating disorders and co-existing depression [14], other mental health conditions [15], diabetes [16], and even surgical preparatory guides [17]. While there is no one-size-fits-all digital health technology, it is crucial to note that in this rapidly evolving technological age, the potential for technologies negatively impacting patient care is definitely something that we need to consider as DHH practitioners, so that we can use our knowledge from the past to better digital health practices in the future.

WarfarINT – Developing Serious Games through User-centered, Experience-centered, and Activity-centered Designs

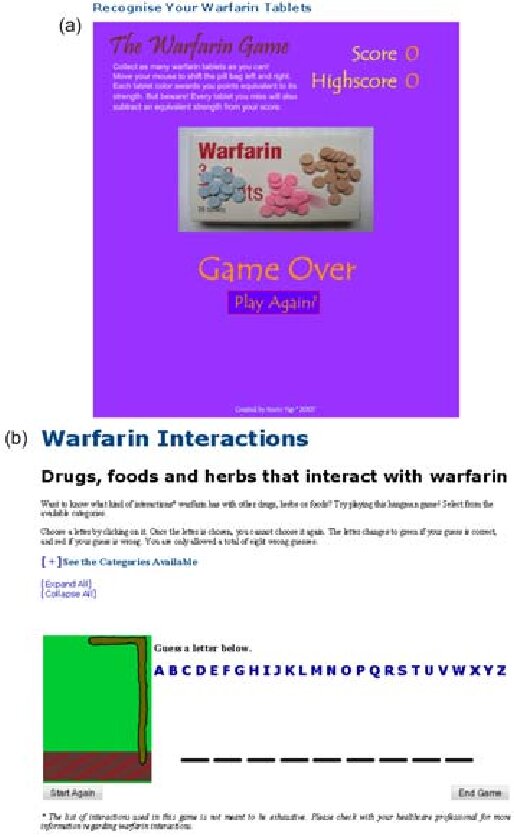

In one of my first papers that I published in human-computer interactions (HCI), I described how concepts in pharmaco-cybernetics could help in serious games design [18]. Through two games that I developed to educate patients on the strengths and colors of warfarin tablets, as well potential drug-drug and drug-herb interactions, I demonstrated how certain concepts (e.g. visibility, mapping, feedback, duration of exposure, behavior, reflection, etc) could be used in the design of healthcare games to influence user experience (Figure 3).

Through this landmark paper, I defined the Pharmacocybernetic Maxims, which described how digital tools for pharmacy and the pharmaceutical sciences should be designed in terms of 4 main principles (Table 1). I advocate that these principles are still, and especially relevant, in today’s world, where there are more and more digital health products that are developed for patient care. Developers of these products should adhere to these principles in order to ensure that their products are of good quality and drug-related problems are minimized or eliminated.

| Design Principle | Explanation of Principle |

| Quality of information | Drug information content provided by the informatics or internet tool(s) should be accurate and follow appropriate resources for evidence-based therapies (e.g. research articles, established databases or product information). |

| Quantity of information | Adequate information about the drug or drug therapy is provided so that users of the tool know enough to minimize the likelihood of drug-related problems (e.g. underdose, overdose, drug interactions). |

| Relationship with target audience | Drug information provided by the tool(s) is/are relevant to what the target audience needs to know, and should clarify their doubts instead of making them more confused. |

| Manner of presentation | Drug information provided by the tool(s) is/are conveyed clearly in an appropriate manner which avoids ambiguity and misinterpretation (e.g. layman language for the patient and medical jargon for healthcare professionals). |

Concluding Thoughts

There’s a lot that we can learn from the humanities that allows us to understand the present and foresee the future. For example, there have been many movies about epidemics and pandemics even prior to COVID-19 [19,20] – for example, Contagion, Outbreak, Flu and even one entitled “Pandemic“. There were even fantasy viruses – the most common being those of zombie viruses – from movies such as World War Z, I Am Legend, and even Train to Busan. We saw the consequences of not properly containing the virus outbreaks, the conflicts of individuals (the main movie protagonists), the blindness of governments in ignoring signs until it was too late, the horrible state of national and global shutdowns, the fear and panic that followed, and even potential hypotheses on how to contain the outbreaks. Looking back, we should have learnt all these lessons from these movies, but as it stands, most of us did not. Now that we have survived a real global pandemic, perhaps it is time to really understand and learn the morals and lessons from these movies, so that we can do better when the next full cycle comes around – perhaps during our lifetime or maybe not. I personally remember suffering through SARS and H1N1 as a young pre-registration pharmacist – being quarantined and experiencing that fear of going near a SARS patient, and thinking that I would never see my family again. This is an experience that I would never wish upon any of the younger generation of healthcare professionals. But how can they learn? With advancements in digital health technologies, perhaps one day, they can live through these experiences in a virtual world, having that feeling of “being there”, yet experiencing it in a safe environment, so that they can be in touch again with their inner selves. Perhaps… Just perhaps… We can bring back the humanity of healthcare practices through the humanistic elements of digital health technologies – in the emerging field of Digital Health Humanities…

References:

- Ostherr K. Digital Health Humanities. In: Klugman CM, Lamb EG, eds. Research Methods in Health Humanities. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2019:182-198.

- UCSF Library. Digital Health Humanities. University of California San Francisco. Available at: https://archive.fo/UaRsr.

- Northeastern University Humanities Center. Digital Health Humanities: A Critical Intervention for a ‘Data Driven’ Pandemic (YouTube video). Northeastern University Humanities Center,. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kalXBgB3jiQ. Updated Apr 2021.

- Chow BWK, Lim YD, Poh RCH, et al. Use of a digital contact tracing system in Singapore to mitigate COVID-19 spread. BMC Public Health 2023; 23(1): 2253.

- Yap KY, Xie Q. Personalizing symptom monitoring and contact tracing efforts through a COVID-19 web-app. Infect Dis Poverty 2020; 9(1): 93.

- Roberts G. Monitoring COVID-19. La Trobe University Science, Health and Engineering (SHE) College News. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/91584487/Monitoring_COVID_19. Updated 21 Jul 2020.

- Tateno M, Skokauskas N, Kato TA, Teo AR, Guerrero APS. New game software (Pokemon Go) may help youth with severe social withdrawal, hikikomori. Psychiatry Res 2016; 246: 848-849.

- Coughlan G, Coutrot A, Khondoker M, Minihane AM, Spiers H, Hornberger M. Toward personalized cognitive diagnostics of at-genetic-risk Alzheimer’s disease. PNAS 2019; 116(19): 9285-9292.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA permits marketing of first game-based digital therapeutic to improve attention function in children with ADHD. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-marketing-first-game-based-digital-therapeutic-improve-attention-function-children-adhd. Updated 15 Jun 2020.

- John Leon Singh H, Couch D, Yap K. Mobile health apps that help with COVID-19 management: Scoping review. JMIR Nurs 2020; 3(1): e20596.

- Goh ASY, Wong LL, Yap KY-L. Evaluation of COVID-19 information provided by digital voice assistants. Int J Dig Health 2021; 1(1): 3.

- Tan RY, Pua AE, Wong LL, Yap KY. Assessing the quality of COVID-19 vaccine videos on video-sharing platforms. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm 2021; 2: 100035.

- Li LSE, Wong LL, Yap KY. Quality evaluation of stress, anxiety and depression apps for COVID-19. J Affect Disord Rep 2021; 6: 100255.

- Koh M, Xie Q, Wong LL, Yap KY. Quality assessment of digital voice assistants on information provided in eating disorders and co-existing depression. Minerva Psychiat. Mar 2021; 62(1): 37-45.

- Chua VKL, Wong LL, Yap KY. Quality evaluation of digital voice assistants for the management of mental health conditions. AIMS Med Sci. Dec 2022; 9(4): 512-530.

- Chia JQE, Wong LL, Yap KY. Quality evaluation of digital voice assistants for diabetes management. AIMS Med Sci. Mar 2023; 10(1): 80-106.

- Gadde NS, Yap KY. Mobile health apps that act as surgical preparatory guides: App store search and quality evaluation. JMIR Perioper Med. Nov 2021; 4(2): e27037.

- Yap KY, Chuang X, Lee AJM, Lee RZ, Lim L, Lim JJ, Nimesha R. Pharmaco-cybernetics as an interactive component of pharma-culture: Empowering drug knowledge through user-, experience- and activity-centered designs. Int J Comp Sci Issues. Aug 2009; 3: 1-13.

- Velasquez J, Raul D. Best movies about pandemics and viruses, ranked. Movie Web. Available at: https://movieweb.com/best-movies-about-pandemics-and-viruses/. Updated 15 Nov 2023.

- Watercutter A. From Outbreak to Contagion, the movies that get pandemics right – or not. Wired. Available at: https://www.wired.com/story/pandemic-movies-tv/. Updated 3 Mar 2020.